I've called this volume Raw forming because it and the

London volume are the long bridge from Mennonite farmer's daughter to experimental

filmmaker. It begins September 1963 when I arrive at Queen's University

on scholarship. The London volume ends December 1974, eleven years later,

when I leave England with the uncut footage of Trapline and a four

year old son.

First year at university [vol 1]

An eighteen year old who had grown up in a narrow religion on a northern

frontier where no building was more than fifty years old and no tree taller

than thirty feet, no white family more than fifty years established and

most of them recently immigrated, is given a ticket - wins a ticket - to

a good eastern university in a limestone city founded in 1673. Her school

community to the age of seventeen had been a stable group of fifteen or

twenty farmers' children. Now she is meeting new people every day and they

are Africans, West Indians, Brits, Americans, big city sons and daughters

of doctors, diplomats, media producers. Her best friend is Welsh and a corporate

lawyer's daughter from Toronto. Her best male pal is son of a national bank

director.

There is a wealth of things she doesn't know. What's a sailboat like,

what's hawthorn like, what's sherry like. In her first year she throws herself

into investigating these possibilities. It's an energetic scan, not sensitive.

She babysits for faculty and scrutinizes their fridges and record collections.

She tries art galleries and classical music concerts. She dances at International

House parties. She drinks wine and she writes her parents about it. She

goes to church but her family is not encouraged by her reports, because

she visits the Catholics, the Episcopalians, the Quakers.

She's exploring mainly the middle class and she's figuring out how to

succeed there, but a boy she meets in the front row of Philosophy 1 comes

across as something else. She likes him but she knows she won't interest

him. It turns out he's from Boston money, but what it is about him is more

than money, it is placement. He already knows everything she will have to

spend years learning. Where she is eager he is cynical. Where she is striving

he is dropping out. He sells her a Ban the Bomb pin and she joins CUCND.

She records nearly everything about her first semester in letters to

her family, typed in tiny elite font on pages her mother files in a binder.

These pages detail weather, personalities, classes, residence life, food,

clothes, college rituals, music, books, and the campus on Lake Ontario.

She flirts with a lot of men and she wants a few of them, but she keeps

a distance.

The writing in the first volume of Forming is quite feverish.

Although I thought of them as a journal, the letters have an overdone animation

as if I'm impersonating a vivacious co-ed for my family's entertainment.

I've edited little of the gush, but have deleted most of the personal comments

directed at family members, both because they are extraneous to the record

and because they sound false. I was writing to a partially invented family,

trying to carry them with me but actually zooming away. Reading the letters

now I also notice how hard I was working to hold down my mother's disapproval

of the directions I was taking - how closed I had to be to her, because

her anxiety could have undermined my courage.

The fact that I was mostly writing letters rather than actual journal

made me blind to the degree of hardship I was experiencing behind my real

and false excitement. My leg spoiled me socially to some unknown degree,

and I laboured to charm new people without knowing I was working against

that tension. I was underfunded by my scholarship, worried about money while

my friends were not. Grades were down, and I was frightened competing with

people who'd had one year more in better high schools. There hadn't been

touch since Frank and I didn't realize how much I missed it, but I gained

twenty pounds in residence, was binging and starving.

What it is about the writing is that it isn't silent. It doesn't touch

into the other side. I was learning the paraphernalia of the world - Gruyère,

timpani, chitterlings, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Welsh cupboards,

Rachmaninoff, Latin graces. I'm now sad to have written badly but at the

same time I honour this raw eighteen year old for doing what had to be done

and doing it headlong.

The Europe year [vol 5]

A girl getting by on energy and charm. She hitchhikes alone through Greece,

Turkey, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Hungary, Austria, Germany, France. Her rides

feed her and she listens to their stories. There are close shaves. She enjoys

escaping by her wits. One time, in Istanbul, she lets herself get boxed

in and doesn't escape.

She sleeps next to the lion gates at Mycene, in a cave above Les Baux,

in a house under construction on the Adriatic coast. She doesn't meet other

women traveling the way she does, but it's 1966 and there are a lot of young

men on the road. She roams the capitals of Europe the way they do, in old

clothes without money. They accept her as one of them. She sleeps with them

if she wants to.

She's all there; she takes people in and they like her for it. In Strasbourg

she befriends a mathematics student from Cote d'Ivoire, a rootless German

who was in the Luftwaffe at 17, an Alsacian widow anxious to hold her rank

among chamber maids in a four-star hotel, a middle-aged American petrochemical

engineer consulting at a French refinery, thinky Jewish boys from Toronto

and Brooklyn, a sixteen year old busboy who spends Christmas Eve with her

in an ancient hotel room. In Rome a Sicilian army recruit, a 14 year old

Rumanian refugee, an art student from LA. In Athens young sisters with whom

she tramps through the springtime city wearing crowns of flowers, French

boys on their way to India overland. In Brussels a titled bachelor with

a flat above the Grande Place.

Greek villagers invite her to a country wedding. An Orthodox priest in

a black robe brings out coffee when she wakes next to the tiny chapel at

Sounion on a Sunday morning. Servants celebrating Easter in a doctor's kitchen

in Agrinion take her along on their Good Friday evening procession through

the town. A Turkish family shelters her on a stormy night in a mountain

village in Yugoslavia. Teenagers in the same village take her to their high

school for the morning. A young French businessman in a silver Aston Martin

takes her to lunch and then plans a route through the Bois de Vincennes

to give her the most beautiful first sight of Paris.

How is the writing. I have a good ear in four languages, there's that.

I take away strong visual impressions and can describe them. But I'm awkward

when I try to play, there's still the painful goofiness of family address.

I think there's also something firmer, though. I had been sure of myself

before, but now I have physical confidence. I have been living day after

day in my body's moment rather than in good-student duties. There has been

constant new experience. I've coped without security, habit, and image.

I'm standing in my own bones more than I have. It shows: I'm better looking.

And some of this physical confidence is there in the writing, I think. Isn't

it that? Something more centred in the tone.

The last years in Kingston [vols 6-8]

I land at Kennedy Airport too early in the morning to go anywhere. Lay

my sleeping bag behind a bank of seats in a waiting room and am woken in

daylight by two black sweepers who confuse me by speaking English.

Get back from the year in Europe full of places, voices, faces that I

know I can never share. Olivia has found us an apartment at the corner of

Division and Princess. By now she and Don have been together a year and

a half and are a solid item. Don is living on Clergy Street with a roommate

he knows from politics classes. I meet Greg Morrison the day I have to fetch

my blue suitcase - the same blue suitcase bought with my first paycheck

at 16 - from the shipping office where it has at last arrived from Athens.

I won't let him carry it, instead hoist it onto my shoulder and walk it

home. He likes that.

Don and Greg have more money than Olivia and I, and we come to an arrangement

that gives us a sweetly familial year. They pay for groceries, we shop and

every night cook dinner in our basement kitchen. Afterwards the men wash

dishes. There is a cat. These hours together every night are home to all

of us. We have a good year, steady, none of the frenzies of second year.

Work hard. My sister Judy is now at York University in Toronto, and my aunt

Anne is in Toronto too with her family. There are visits back and forth,

and stays with Greg's parents in Ottawa.

Don and Olivia get engaged at Christmas. In early summer, after final

exams, they are married in Toronto. Afterward my plan is to stay with my

family in Alberta for the summer, working on two reading courses. I last

until the middle of July, flee back to Kingston and live with Greg until

school begins again.

Don has a scholarship to do a PhD at Oxford and I see him and Olivia

off at the dock in Montreal. Greg's roommate at 40 Clergy Street is now

Michel de Salabery, a French Canadian politics student with Gallic courtoisie.

I have a room at 15 Sydenham but am almost never there, eat and sleep with

Greg. Am now in my last year: learning psychology, existentialism with Martyn

Estall, nineteenth century philosophy with Michael Fox, Victorian literature

with Kerry McSweeney, European cinema with Peter Harcourt. In this semester,

from one moment to the next I decide to be a film maker not a child psychologist.

There's a heavy exam period at the end of this year, because I have general

exams in three subjects as well as the usual five. When it's done Greg and

I move to a summer sublet beside the yacht club, and then drive south in

his mom's Triumph to camp on the beach at Hunting Island in South Carolina.

Come back to a job with Hugh Lawford's international treaty project.

In September I move into a little apartment on the second floor of 30

William St overlooking the Wolfe Island ferry dock. Most of my friends have

taken their next steps and are no longer in Kingston; 9 to 5 work does not

suit me; Greg is finishing his MA on alienation and soon to leave for a

PhD at the London School of Economics. I go into a baffled eddy. Sexual

investigation, or call it sexual craziness: affair with my married film

professor, other affairs, miscellaneous. Three months in Kingston General

Hospital in a body cast recovering from hip reconstruction. The best thing

in this year is that my salary at the treaty project buys me a Nikon Ftn.

In July of 1969 I go to London with Peter Harcourt and don't return when

he does.

Studies

I graduated with a General Honours triple major in philosophy, pyschology

and English and electives in French, German, art history, music history,

and film.

Philosophy 1 was required in first year and I liked it but didn't begin

philosophy as a major until third year, after the year away. I had native

philosophical talent, which was my ability to focus down, to ask, What's

this really about? I could get to the essence of a question. I couldn't

do it in class, I never spoke in class, but I could do it when I was writing.

I also had a talent for coming sideways, often through something I found

in a book on some other topic. I'd say, This is relevant, and then I'd find

out how to use it. What I liked best in philosophy at Queens was existentialism

and Hegel. I took on the existentialist notion of bad faith and authenticity,

which supported my own intuition about ethics - that clarity and truth-telling

are what matter most to human well-being, both personal and general. De

Beauvoir was my first feminist. I loved Sartre and de Beauvoir personally,

as essential helpers in life. What I liked in Hegel was his huge dark being,

so intuitive, so tactile and full. I loved that I could understand him.

I liked his sense of spirit coming into its powers through the eons. I loved

who he was. I loved thinking about consciousness.

I wasn't as good in English because I didn't have literary grace in my

writing. Philosophical clarity was my strength in English too. I'd get A's

but I wasn't the best. It startled me to see that someone like Dorris Heffron

was better than me.

In psychology I liked the parts that were philosophical and observational,

stories about lives and beings, but I loathed statistics and the experimental

method. I knew graduate work in psychology would be more of that, and so

that road was closed.

The year before I went to London I discovered Doris Lessing, The golden

notebook first. What it was about Lessing was that she was current,

describing the life we were living and showing us how to think about it.

She brought us her Communist training in consciousness raising: how to think

further about power relations. She demonstrated intimate personal combat.

She was an example of energetic high intelligence alive in an unacademic

mode. Other books that mattered were the Alexandria Quartet, Wilson's

The outsider, Agee's Let us now praise famous men, Mary Renault's

Greek novels, Updike's Pigeon feathers, Hebb's The organization

of behaviour, and Unterrecker on Yeats.

Film at Queen's was Peter Harcourt, who arrived to set up the first film

department in Canada as I was going into third year. At first I was more

interested in Peter than in film because he showed me it was possible to

speak directly, intimately, personally in public. I wanted to learn to do

that. He thought I had talent as a film critic, and he set me up to write

movie reviews for the Queen's Journal. I wrote about feature films

- Pierrot le fou, Poor cow, Isabel - but documentaries

were more my thing. The NFB's Skating rink, Don Levy's Time is.

Films that were just seeing, a way of showing seeing as such.

When I graduated Martyn Estall got me the medal in philosophy and a Woodrow

Wilson nomination to do philosophy in the US, but the philosophy of the

time, British and North American analytic philosophy of the late 1960s,

seemed bloodless to me. I went to London to do film instead.

|

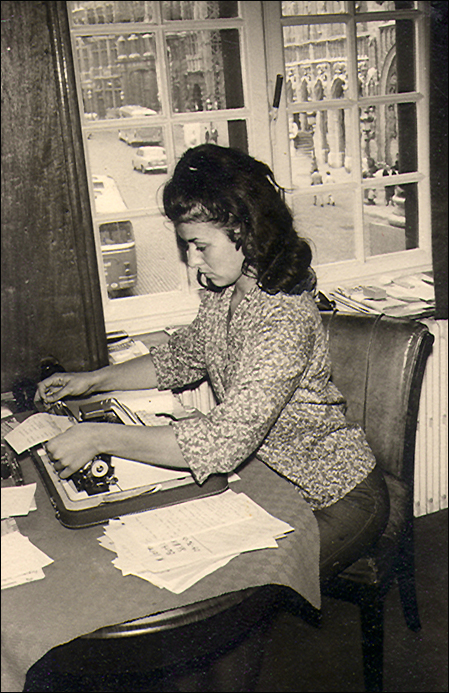

- above the Grande Place in Brussels,

photo by a Stars and Stripes photographer

- above the Grande Place in Brussels,

photo by a Stars and Stripes photographer